A man, a plan, a Eurorack modular

As someone who has made their way through a variety of synthesizers, samplers, effects, mixers, and other machines that go bleep in the night, I’ve never gone into too much detail about modular synthesizers. It was watching Radiohead perform Idiotque on Saturday Night Live in 2000 when I first got my first glimpse of a modular system, though at the time I had no idea what I was looking at, only that it was gigantic, made some rather interesting noises, and required fistfuls of wires to operate.

Modular systems, especially Eurorack, have become much more accessible over the last couple of years. It’s no secret that they’ve been used to make noise, and some would even say music, well before the invention of the traditional synthesizer with a keyboard attached to it. Their use amongst avant-garde and even popular musicians is acknowledged today, if you’ve ever heard a Donna Summers song you’ve probably heard the sound of a modular synthesizer (thanks to Giorgio Moroder).

Given all of the different functionalities you can achieve by using a modular it is no wonder its popularity has taken off. Fortunately for us (and the modular manufactures), electronic music currently exists in a state where the more obscure your gear is the more heralded your genius is as an artist (the “Aphex Twin effect” so to speak). The more you make your music look like analog wizardry the more curious people will be about your craft.

Complete modular systems can run into the tens of thousands of dollars, which is no surprise if you take into account the burgeoning number of modules available to you, not to mention the complexity of the workflow and sheer amount of choices you can (theoretically) have when it comes to building a patch. If you had your heart set on it you could even replace an entire studio and digital workstation with just rows upon rows of knobs, jacks, and wires. For some, this may feel completely impractical and vulgar, but that hasn’t stopped some from giving it a go.

I initially considered getting into Eurorack because I already own a few pieces of semi-modular gear (Roland SH-101, Mutable Instruments Anushri, KORG Monotribe, and an Elektron Analog Four just to name a few) which can interfaced with CV and Gate signals sent from a modular rig. Getting to learn more about building a complete system as well as figuring out the intricacies of patching was also a lure for me to go deeper. With the cost of getting started being what it felt like a difficult decision to even want to get started down the modular path, but I told myself I would only commit to buying those modules which helped me execute on specific tasks in the studio, anything else would just be money wasted and time lost. But what other constraints could I put on myself to make this adventure more manageable and efficient? The last thing I wanted to do was waste my time and money hunting a wild goose.

Much planning ensued.

I can’t stress enough just how powerful resources like Modulargrid.net and the Muff Wiggler forums were when researching all there was to understand about general modular concepts as well as individual modules themselves. Many of the initial questions I had were already discussed at length on some of the forums, but there was so much else to learn whether it was reading about comparison of similar modules, hearing the music others had created, or seeing pictures of the systems other enthusiasts had built. Everything I came across lent itself to helping me realize what kind of rig I might want to put together someday.

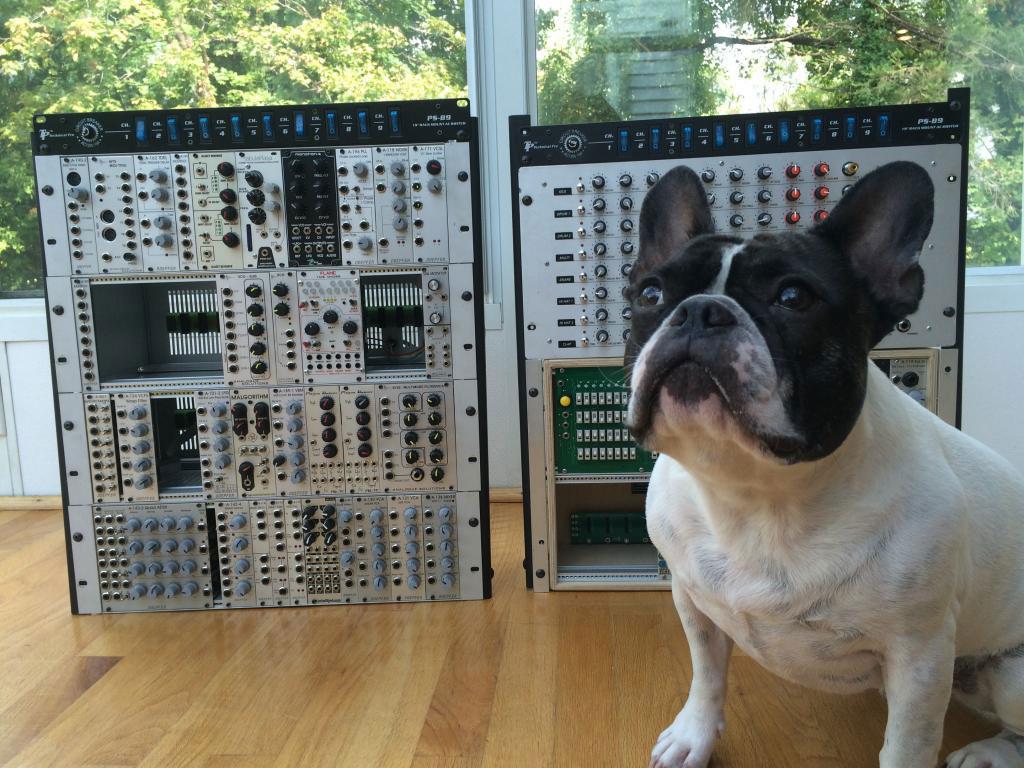

After browsing numerous threads on Muff Wiggler, I began to piece together the first few concepts I had for my own modular system. First and foremost I wanted my system to be capable but also remain lean, this wasn’t just due to the cost of the format but also due to my desire to keep things simple, not to mention I hoped to be able to take my rig with me and that’s not quite an easy thing to do when you entire living room is stacked from floor to ceiling with hardware. Second, the modules I choose should be ones which I can understand the functionality of. If I point to a module and can’t give you a single sentence answer to the question “what does this do?” then it doesn’t belong in my system.

Being able to run a smaller system also means having to delicately choose modules based on how much (or how little) space I have available. I don’t need to own the biggest and best modules in order to create something enjoyable, but the more features and functions I could squeeze into an already tight amount of space would mean a great amount of possibilities are available to me. In terms of functionality, I only wanted Eurorack that would expand upon the capabilities of my studio, I did not want my modular case to overlap too much with the gear I already owned. Perhaps when I get better acquainted with Eurorack and can bend it to my will I will break this rule slightly, but my goal here is to achieve functionalities I can’t get from mere studio hardware: to shape, sequence, modulate, shift, decimate, manipulate, and otherwise mangle sounds in a manner previously unknown to me.

There’s no doubt I’ll add an oscillator or two down the road given some of the amazing concepts already available for making noises with one’s rig, but for the time being I plan to focus on using the noise makers I already have in the studio that can interface with modular gear (and possibly modify some other synthesizers so they can use CV and Gate signals). Thinking about my modular rig in this way, I’m already putting constraints in place to help me save money and space I’d rather dedicate to more important equipment such as function generators, waveshapers, sequencers, quantizers, grain loopers, and clock distributors. The oscillators, filters, VCAs, and drum modules can wait!

Finally, in an effort to truly make my rack a product of my own creation (and to save on a little bit of money), I plan to build whatever modules I can from DIY electronics kits. When I first began to research what was available I was surprised at how many modules could be sourced by just buying a kit and soldering the parts in myself. Considering the roots of modular synthesis, the DIY and experimental mentality it took on in the early years, it’s great to see the spirit is still alive and well with today’s designers and musicians. Sites such as Thonk.co.uk, Hexinverter.net, Synthrotek, and Synthcube offer a diverse selection of projects either as complete kits or as panel and PCBs combos (where you still have to source all the parts yourself). For starters, the Thonk Turing Machine, Synthrotek PWR and ECHO, 4ms Pingable Envelope Generator and Rotating Clock Divider, and a bunch of the Manhattan Analog gear are already on my wanted list.

Though it feels like modular synths might be kind of a trendy thing right now, I’m glad I have the opportunity to take the plunge and do it in a very intentional way. If my plan works out and I really jive with the format then I imagine I’ll have a variety of modules in my studio for a long time (even after the current popularity wears off). With all of the limitations I’ve put on myself it will be necessary to get creative with my module and patching choices, but limitations help breed creative solutions, and when it comes to something new like Eurorack, I’ll take creative approaches wherever I can find them.

This page was last updated on October 14, 2014.