Constructing a complete drum kit

Drums are the basis of any great track. Many times when crafting a song you’ll find yourself dealing with the rhythm of the track first. To some extent the rhythm ends up dictating the majority of your tune, it sets the tempo, the timbre of the individual drum hits creates a specific mood, even the act of adding or taking out specific drum tracks creates the skeleton of your song, laying out where other sounds will come into the mix, making their appearance.

When arranging your tune it’s obviously important to create an addictive rhythm, endlessly driving the music and backing up the rest of your composition, but almost equally as important is being able to craft a cohesive kit of drum sounds which will be utilized completely in your production.

Having an assembled drum kit right at your fingertips can be an incredibly inspirational experience. Too many times have I pulled out my MPC or Machinedrum only to start picking out a good bass drum and snare, laid down a basic rhythm, and then have gotten lost in the endless possibilities of adding more percussion or tweaking what I already have. Do I want to add some hi-hats next? Crazy ethnic drums? What kind of mood am I even going for with this tune?

Having that great kick-snare combination going while desperately searching around for other sounds that will play nicely with the track can be a little exasperating, especially if you have a huge unwieldy sample library. To avoid interrupting my workflow like this, I’ve taken to the habit of laying out an entire kit of drums first before I even record a single note.

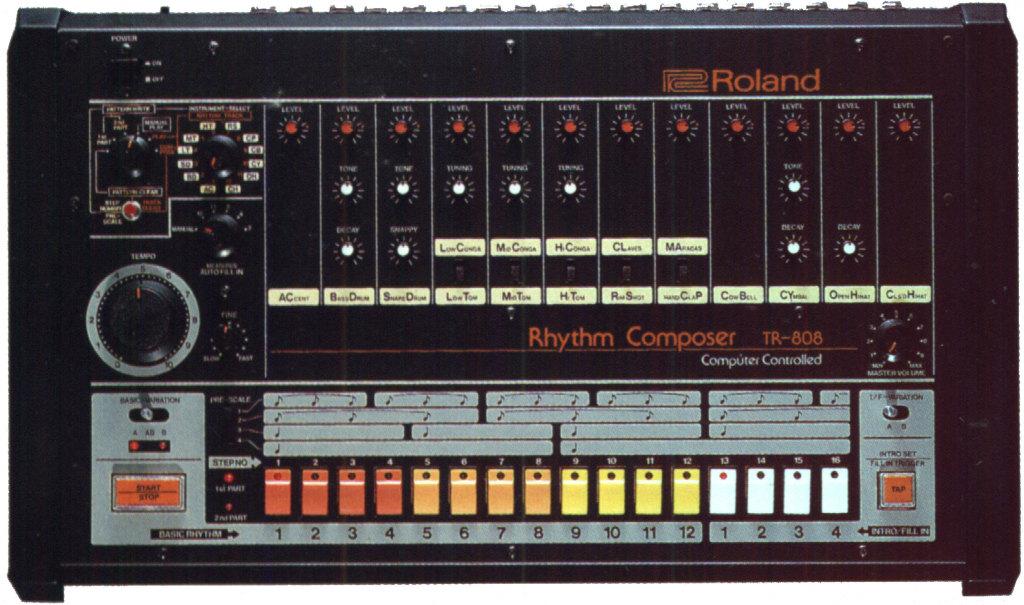

There’s a reason entire genres and even entire careers have been built off of using machines like the Roland TR-808 or TR-909. Yeah sure they sound good, but they also helped eliminate a lot of the barriers to getting started on a track. Just plug in your 808 and start sequencing. It’s going to sound good no matter where you place your beats and it gives you every element you need to lay out a basic drum track.

Among other advantages to working with a complete kit, you’ve already established the array of colors you’ll be painting with on your track. Working with just black and white can lead to a complete track as well, but going into your production with a full arsenal of sounds that you know work well together helps avoid one of the major derailments that can happen when getting started on a new track, namely, getting lost in endless possibilities.

That is not to say it’s easy to craft an entire kit, in fact it’s quite time consuming and I still find myself swapping samples in and out of many kits I’ve made, but even though each drum sound might not be 100% perfect, having all the necessary elements laid out in front of you takes a lot of the pain out of process. Specific kits also fit specific genres. Are you in an Acid mood? Just call up your 808/909 kit. Going for something more electro inspired? Call up your electro kit.

Making music should be fun and inspiring, and sure there’s a lot of work involved, but the more exact you are in your preparations the less hassle you’ll encounter and the easier it will be to pump out great tracks you’ll be satisfied with.

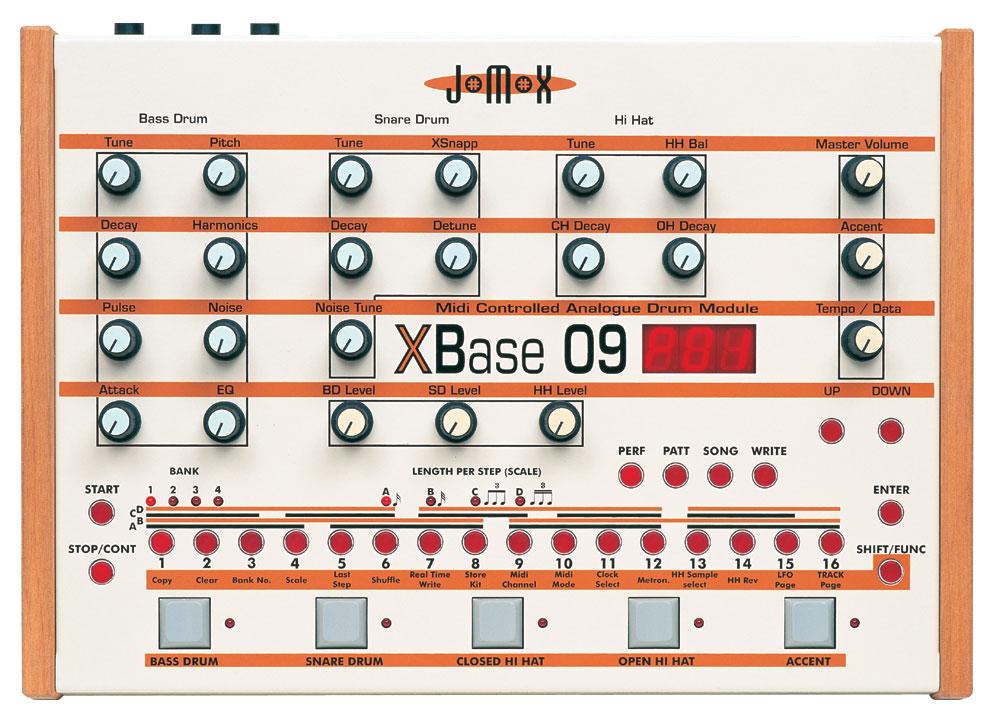

Since there are almost too many ways to construct a kit of drum sounds (be it in your DAW, a VST, drumming on an MPC, sequencing individual drum hits from a variety of hardware, or some combination of these) I’ll be coming at this kit construction concept from the method that works best for me, namely, assembling your drum kit in a single piece of hardware. I like this approach because it puts some constraints in place, gives me a boundary I have to work within, though depending on the instrument of choice, you’ll still have more than enough headroom to play with.

Working within a single piece of gear also means that I can easily take my work with me, either for a performance or a friendly jam session, all of my sounds and patterns ready to go. For this task I like to use my Elektron Machinedrum but my MPC-1000 also pops it head up depending on what kind of mood I’m going for. You can use any piece of hardware or software you’d like, the important thing is that you have multiple tracks to work with and the ability to craft different timbres in a single device.

On the Machinedrum there are 16 tracks we can utilize. Some drum machines will have fewer, some drum machines will have more, it all comes down to personal preference. To start, let’s take a look at the basic template of a rhythm kit:

-

Bass drum

-

Snare drum

-

High tom

-

Middle tom

-

Low tom

-

Open hi-hat

-

Closed hi-hat

-

Crash cymbal

-

Clap

-

Cowbell

-

Rim shot

-

Shaker

This combination of sounds is a tried and true format. Remember, this is just a basic template, don’t let your music be dictated by some established standard that’s been around since the beginning of time. That being said, there’s a reason these 12 rhythmic sounds have maintained as a standard in electronic music and many other genres. They work! In another post I hope to talk more about how each of these elements play off of one another to create a beat that makes people want to move, but for now though let’s look at each of these sounds and their utility to a track.

First and foremost we have the Bass drum (BD) and Snare drum (SD). Both these elements derive from your typical acoustic drum kit and work so well to establish rhythm due to their presence and complimentary tonalities. The low boom of the BD keeps the repetitious time of a track (“4 On The Floor”, for example), sitting well below every other drum sound, while the SD accents parts of the rhythm, creating a bouncy smack that breaks up the monotony of the BD. You can tune these elements however you’d like but generally the BD will stay in the lower registers while the SD sits in the middle frequencies of your drum mix. If your drum machine allows it, it’s even a good idea to have two BD or two SD sounds in your kit because of how central they are to creating rhythm.

Next we have the toms section: High Tom (HT), Middle Tom (MT), and Low Tom (LT). As individual drum tracks, there are many uses for these 3 slots. Of course you don’t need one, two, or any toms in your kit necessarily but the toms section allows you to create a polyrhythm or additional rhythmic element by taking the same drum sound and giving it 3 different tunings. If you’re going for the typical usage of the toms it’s important to tune each drum so they work in harmony and their frequencies don’t clash. You can create interesting triads with specific tunings on each tom tom or a variety of other effects. Musical theory comes in handy for designing specific tunings but a decent ear also goes a long way.

To round out our punchier percussion sounds we turn to some more metallic, higher frequency sounds like the Open hi-hat (OH), Closed hi-hat (CH), and Crash cymbal (CC). The OH and CH of course create a syncopated rhythm on top of whatever groove is currently playing. The CH especially can be used to “capture” a groove due to its subtle but driving qualities, sitting in the background of the overall rhythm but adding to the infectiousness of the beat. Letting the CH ride on every 16th note is a classic example of this in techno. You can also use the CH to create a sort of a gated rhythm by applying it to every 16th note and then removing only a few of these notes in your beat. In the Machinedrum I can even do this via an LFO. I like my Machinedrum.

These two sounds should be tuned similarly and I’d recommend using sets of OH and CH sounds instead of any old hi-hats. The intonation of both of these sounds is important to getting your hats sounds right. After all, 1 drum produces both these sounds in an acoustic drum kit. You’ll find the CC useful as an accent element, usually coming at the end of a measure to sustain a particular rhythm. There is a great deal of variation out there with the CC since your typical drum kit crash has so much presence and ride (more suitable for rock music). It worked for some tracks (lots of early techno) but you may be going for a different atmosphere with your CC.

Finally we have some extra percussive elements that will mix nicely into your rhythm, either to help create some variation, backing rhythm, accent, or a completely different drum beat altogether. Clap (CL), Cowbell (CB), Rimshot (RS), and Shaker (SS) play this role, but don’t let the names fool you. The term “percussion” spans so many types and sound sources that it’s impossible to break it down to something as basic as the kick and snare relationship. With these additional sounds you get an extra layer of refinement and variation over your (presumably) bare-bones drum pattern. In my example I’ve used these elements to create alternate rhythms that blend into the original beat and can be used on their own as fills or a drum relief.

Many times I’ll use these tracks for 1-shot samples, wacky LFO modulated percussion, alternately tuned versions of other drums, or even, specific to the Machinedrum, as MIDI tracks to control other machines with. CL and CB can be especially effective as-is due to their established sound in much of modern music, and depending on what machine you’re working with, you may find a lot of beautiful harmonics while tweaking your CB sound.

As you develop your drum patterns and find the need to re-tune or even replace certain sounds you’ll still be miles ahead in your work in contrast to starting out your pattern with just one or two sounds in your kit. Programming your drum patterns can be a good deal of fun but the real rabbit hole comes when you begin to tweak each individual drum sound to suit the rhythm and layers of your other parts. Drum patterns can come a dime a dozen but a cohesive and battle-ready drum kit is a much more valuable resource to have at your fingertips.

I hope this article has given you a wider basis to start crafting your kits with and provides a forest-from-the-trees perspective on drum machine workflow.

This page was last updated on October 04, 2014.